Encountering Souza

This month (June 2025), I attended a session titled Souza Modernism, held at the Bangalore International Centre in Domlur, which focused on the artist F.N. Souza1. The discussion featured Janieta Singh — author and art critic who has written a book on Souza — alongside designer and art historian Annapoorna Karimelev.

Following that event, I had a brief conversation with writer, photographer, and modern art and literary critic A.V. Manikandan, which I am documenting here. In the first part, I share my reflections and questions about Souza, and in the second part, I include Manikandan’s detailed responses, which offer a broader perspective on Indian modern painting as a whole.

Approaching F.N. Souza — who is considered a key figure in shaping modern Indian art — is not easy, especially without formal education in fine arts or art history. So it’s difficult for me to immediately conclude whether I consider him an important artist or what I think about his work. To make such an evaluation, I would need a foundational understanding of the evolution of modern painting in India. However, driven by my interest in painting and my limited exposure to modern art, I attempted to engage with his work through the aesthetic sensibility I’ve developed over time and through further reading on Souza.

Figuration and Evocation

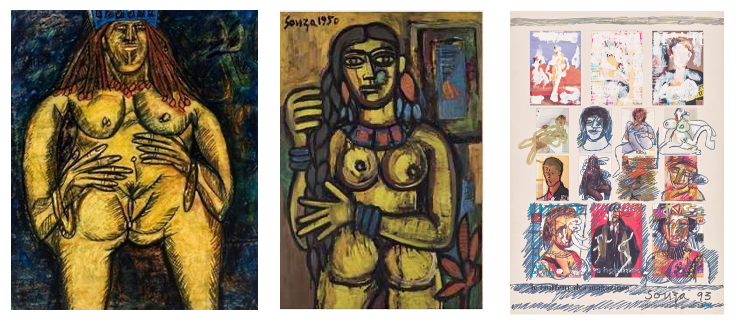

Modern art always poses a challenge for me in terms of how to approach it. Abstract2 works can be especially difficult, while figurative works are slightly more inviting. Since much of Souza’s work is figurative, I was immediately drawn to it. Personally, I find Cubist3 or Expressionist4 work more real than realism — because of its sheer evocative power. Souza’s work is certainly evocative, expressive, and brutal. His forms are charged with bold lines, strokes, and paint daubs — it feels as though they were painted in anger or with anguished emotion.

His recurring themes — religious iconography, the dichotomy of good and evil, and the human body — are close to my own interests, which naturally made me respond to his bold figurative expressions. Yet I couldn’t explore his work deeply until a comment by A.V. Manikandan helped me open it up. AVM said that Souza’s work is the opposite of the what we discussed as Advaitic/metaphysical vision in one of the previous conversation. This initially confused me, especially when I saw Souza’s Catholic paintings of Mary and Jesus and his incorporation of Hindu religious motifs. This led me to explore Souza’s work further.

Naked truth

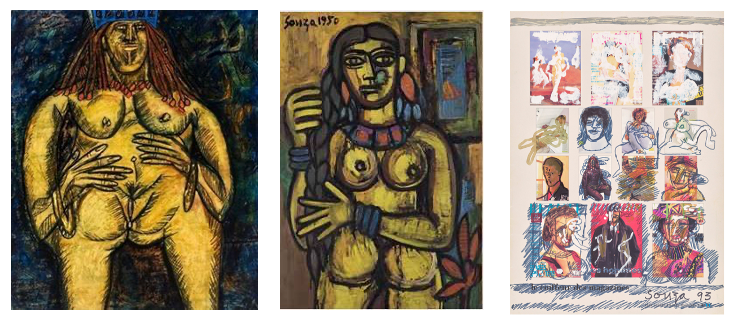

If I simplify the Advaita idea as non-duality, seeing the perceived world as illusion, and liberation as something that happens in a transcendental realm, then Souza’s world is a stark contrast: full of materiality, objectivity, fragmentation, and flesh

His female nudes are unapologetic, erotic, even grotesque at times. As a continuation of artists like Monet and Matisse, his nudes boldly express sexuality — unapologetically and without being defined by the male gaze5. In one of his paintings, a child is handed to a naked mother — a composition resembles religiosu icons. Yet, the woman is drawn erotically — unashamed of her body — asserting bodily presence against any transcendental ideal. For Souza, “the naked body is the only truth.”

Religion Made Flesh

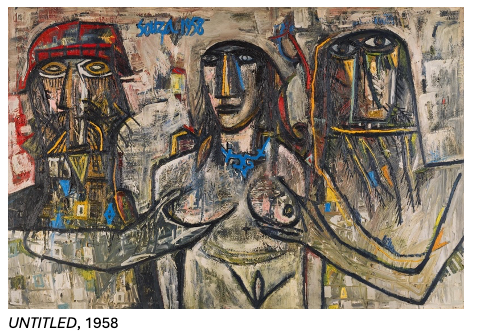

The erotic and naked body is extended in his paintings with religious themes. He combines religious iconography with the erotic, rendering sacred figures more earthly than spiritual. This is most evident in his paintings with Catholic subjects. By juxtaposing raw sensory, bodily experience with religious motifs, Souza de-spiritualizes and sexualizes glorified subjects. I see this iconoclasm6 as a form of anger toward the clergy and religious institutions — but not necessarily against religious philosophy. Christ is often depicted as a suffering man in his paintings. Pain and suffering are foregrounded, rather than redemption. His grotesque representations serve as criticism of hypocritical institutions — in his words, “corrupt and outdated medieval religion, the Roman Catholic Church in Goa.”

The above painting is untitled but as we can clearly see it’s a reference to Susanna and the Elders7 painting based on the biblical tale. In this painting Susanna doesn’t look scared. Either she was stunned or corrupted by authority.

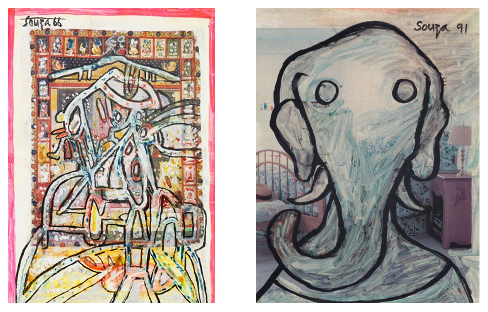

Souza frequently experimented with Hindu iconography too. In his Ganesha paintings, he combines the grotesque aesthetic from his Heads with his religious themes. Ganesha appears fragmented — not whole — but still vivid and alive. It’s not reverence; it’s confrontation. It questions how forms hold meaning even when distorted.

Head Series: Identity Under Crisis

He explored crises like inner turmoil, post war humanity with his head paintings. Some of them are looks insects, some of them defies any gender, race, class identity, some of the looks corrupted. He continuously responded to the everchanging world and mocked it for its contradictions and corruption.

Open Questions

But many questions remain. His female nudes could be seen as a continuation of efforts to resist the male gaze — expanded through an Indian perspective (perhaps inspired by Khajuraho8 or temple sculpture). In religion, perhaps it was his personal trauma and iconoclastic drive that led him to scrutinize religious themes. Yet how might an Indian viewer — already accustomed to nudity in artistic tradition — respond to his use of poses like Lajja Gauri9? Is Souza de-spiritualizing the iconography, or superimposing religious symbols onto modern nude subjects?

Similarly, how might a European viewer read his critique of Christianity — where such themes have already been heavily explored? In other words, what is unique about Souza’s questions? Where is the decolonization happening, as some critics claim?

Souza is metaphysical not because he believes in higher worlds, but because he interrogates the very ideas of God, soul, sin, and salvation — through brutal, carnal, distorted imagery. Even gods bleed in his paintings. Is his metaphysics one of tragedy, violence, eroticism, and struggle? If so, what does the viewer experience through it? An inescapable, dark reality?

The following is A.V. Manikandan’s comprehensive analysis

Souza grew up in the Catholic milieu of Goa. In his youth, he was sexually abused by a priest. When he revealed this, his mother did not believe him. He came to understand that religious faith often demands blind belief and that beneath such beliefs lie suppressed, burning human desires.

His early paintings depicted the landscapes and everyday life of Goa. At that time in Mumbai, an art movement was emerging. This movement stood in contrast to the Bengal School’s return to tradition — it believed that Indian modernism must move forward. Three Jewish journalists and art critics who had arrived in Mumbai from Europe exposed these painters to the currents of European modernism. The artists felt that Indian art needed to move forward and engage in a conversation with Europe. They became known as the Progressive Artists’ Group10, and Souza was one of its pioneers.

Souza was influenced by these developments and began working by embracing the expression of personal emotion and the figurative expression of modern formalism. It was during this wave that he began to render religious symbols in a modern and particularly distorted form. Medieval artists depicted priests and humans like angels. Souza said he painted them this way to show how they really are today.

Due to a controversy over one of his nude paintings, he left India and moved to England. John Berger’s11 review of his exhibition brought him attention in the European art world. However, this also marked the beginning of his personal decline. He adopted Berger’s line — “straddles several traditions but serves none” — as his identity. But from there, he didn’t probe or move further. He claimed that after Picasso, there was no one left to do figurative art and that artists had moved to abstraction- and that he was the one who took it to the next stage. He declared himself the most significant event in Indian art after Ajanta12.

After the trauma of sexual abuse, he could have identified with the oppressed. At the time, the Harijan (Dalit) movements were active. If he had wanted to explore human darkness, he could have turned to Gandhi — who confronted it and was right before him. Instead, he chose to become a hedonist and did not connect with any cultural roots — not even with Western traditions.

That hedonism turned him into a rebel against Indian Catholic morality and an iconoclast against Indian public sensibility. Neither of these were new in the West. While it may have been a significant contribution in the Indian context, it ultimately veered emotions toward dramatization and narcissism. It didn’t offer answers to the questions posed by Indian modernism. Artists like Francis Bacon13 and Louise Bourgeois14, who worked with similar subjects, extended their personal suffering into collective human suffering. Through this psychological perspective, they have become more significant contributors than Souza. Today, he remains a rootless rebel in both cultures.

Where does his work stand today from a philosophical perspective? What is his philosophical foundation? Did he engage with any Western philosophers?

In the Indian art world, very few worked with a philosophical perspective — the same is true in the West as well. Most often, this connection happens when writers engage in close conversations with artists. Jackson Pollock15 worked purely on intuition. Clement Greenberg16 provided him with a philosophical foundation.

In the Indian context of that time, the only art movement that worked with such a philosophical vision was the Bengal School17. After that, another such wave did not emerge until the Baroda School18(e.g., K.G. Subramanyan). Amrita Sher-Gil19 operated on her own as an individual.

The Progressive Artists’ Group regarded art as an artist’s emotional expression, in opposition to the Bengal School’s search for a national identity. So they were a faction opposing the philosophical approach. Philosophy involves positioning oneself with an identity (like Indian/colonized slave/oppressed) and engaging in a conversation with the holistic identity of culture (like world citizen/modern human) as a counterpart. But the Progressive Artists’ Group rejected both ends — subjectivity/self and culture — and focused solely on personal feeling. This led them toward narcissism and dramatization.

Very few escaped the Progressive movement, like S.H. Raza20. He too was someone who went and settled in Europe. He was popular there even before Souza. But he realized that he could not fully belong to the European art world. He understood that simply distorting figures or painting abstracts would not make him part of the European artistic tradition. Later, he studied Indian philosophy and connected European formalism with Indian spirituality. In a way, his paintings are the Indian version of Rothko21.

In contrast, Souza had a self-centred expression. His world was somewhat close to Nietzsche’s philosophical world. But Nietzsche22 was not merely an iconoclast. Though he presented a godless world, he proposed the creative force instead. For this purpose, he brought the language of philosophy closer to poetry. He transformed that creative vision into language. To an extent, we can call Francis Bacon a Nietzschean expression in visual arts. Bacon expressed the limits of human suffering in figurative23 paintings. He discovered new formal expressions that manifested death and revealed that humans are merely flesh.

So only when a philosophical perspective — and the transformation it brings in one’s art form — happens at both levels, can it be considered a contribution with a visionary perspective. Both of these did not happen in Souza. For him, the cross was merely a religious icon. He used it only in a sensual sense. But Bacon saw the cross as a symbol of human suffering. He transformed the cross to express humans being trapped there by removing Christ. This crucifixion possessed a new secular form distinct from prior depictions in European history. By displaying the human body as a cross, he expressed existence as human suffering.

Souza was in close contact with Bacon; they even exhibited their artworks together. But he didn’t absorb anything from Bacon. Unlike Raza, the question of “Where is my place in the European context?” did not arise. Even from Europe, he was constantly in conflict with the Indian cultural milieu, assumed a place for himself in it — and disputed for the same cause. Achieving success in art — being accepted by the world — is as easy as it is difficult. The real challenge is to continue pursuing the questions without being influenced by success and maintaining one’s intensity. For that, one’s ego should not overtake their artistic pursuit.

As Tarkovsky once said: “You should belong to art, it shouldn’t belong to you. Art uses your life, not vice versa.”

Glossary

- F.N. Souza (Francis Newton Souza)

(1924–2002) A pioneering Indian modernist painter and founding member of the Progressive Artists’ Group. Known for his bold lines, distorted forms, and provocative themes — especially religious iconography and eroticism. ↩︎ - Abstract Art

Art that does not represent recognizable subjects, focusing instead on shapes, colors, and forms. ↩︎ - Cubism

An early 20th-century European art movement pioneered by Picasso and Braque. It breaks objects into abstracted, geometric forms to depict multiple perspectives simultaneously. ↩︎ - Expressionism

An art movement emphasizing emotional experience over physical reality. Often involves distortion, exaggeration, and bold colors to convey psychological states. ↩︎ - Male Gaze

A term from feminist theory (coined by Laura Mulvey) referring to the depiction of women from a masculine, heterosexual perspective, often objectifying the female body. ↩︎ - Iconoclasm

The rejection or destruction of religious images or symbols, often used metaphorically to describe the subversion of traditional or sacred cultural symbols. ↩︎ - Susanna and the Elders

A biblical tale popular in Western art history, involving a chaste woman wrongly accused of adultery. Artists often use this theme to explore voyeurism and the female nude. ↩︎ - Khajuraho Temples

Group of medieval Hindu and Jain temples in Madhya Pradesh, India, known for their intricately carved erotic sculptures — often cited in discussions of Indian attitudes toward sexuality in art. ↩︎ - Lajja Gauri

A fertility goddess from ancient Indian iconography, often depicted nude with a lotus in place of her head. The pose symbolizes birth, fertility, and sexual power. ↩︎ - Progressive Artists’ Group (PAG)

Formed in 1947 in Bombay, this collective rejected nationalist romanticism and embraced modernist styles influenced by European movements like Cubism and Expressionism. Founding members included F.N. Souza, M.F. Husain, and S.H. Raza. ↩︎ - John Berger

(1926–2017) British art critic and novelist. His influential 1972 book Ways of Seeing changed how visual culture is understood. He reviewed Souza’s work positively, which boosted Souza’s visibility in Europe. ↩︎ - Ajanta Caves

Ancient Buddhist cave paintings (2nd century BCE to 480 CE) in Maharashtra, India, celebrated for their narrative murals and sophisticated technique. Often cited as a pinnacle of classical Indian art. ↩︎ - Francis Bacon

(1909–1992) British painter known for his emotionally intense, grotesque, and often violent imagery. His work explores themes of suffering, death, and existentialism. ↩︎ - Louise Bourgeois

(1911–2010) French-American sculptor and installation artist known for deeply personal work addressing trauma, the body, and psychological suffering — often considered a feminist icon in modern art. ↩︎ - Jackson Pollock

(1912–1956) American painter and leading figure in Abstract Expressionism, known for his “drip paintings.” ↩︎ - Clement Greenberg

(1909–1994) Influential American art critic who championed modernist painting, particularly Abstract Expressionism. Provided intellectual backing for artists like Pollock. ↩︎ - Bengal School of Art

An early 20th-century Indian art movement led by Abanindranath Tagore that sought to revive traditional Indian styles in reaction to Western academic art. It emphasized spiritualism, symbolism, and a national identity. ↩︎ - Baroda School (Faculty of Fine Arts, MSU Baroda)

An influential institution in post-independence Indian art, known for its interdisciplinary engagement with philosophy, literature, and traditional Indian techniques. Prominent figures include K.G. Subramanyan and Gulam Mohammed Sheikh. ↩︎ - Amrita Sher-Gil

(1913–1941) A pioneer of modern Indian art, known for merging Western styles with Indian subjects. Often called “India’s Frida Kahlo,” she worked independently outside organized movements. ↩︎ - S.H. Raza

(1922–2016) A founding member of the PAG who later integrated Indian spiritual and symbolic traditions (like the bindu motif) into his abstract work after studying Indian philosophy. His work is sometimes compared to Rothko. ↩︎ - Mark Rothko

(1903–1970) Abstract Expressionist painter known for his large fields of color intended to evoke emotional or spiritual experiences. His work is often described as meditative or transcendent. ↩︎ - Nietzschean Philosophy

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) emphasized the death of God, critique of religion, the will to power, and the creation of individual meaning. His influence is visible in existential and modern art. ↩︎ - Figurative Art

Art that clearly represents human or animal forms, as opposed to abstract or non-objective work. ↩︎

Leave a comment