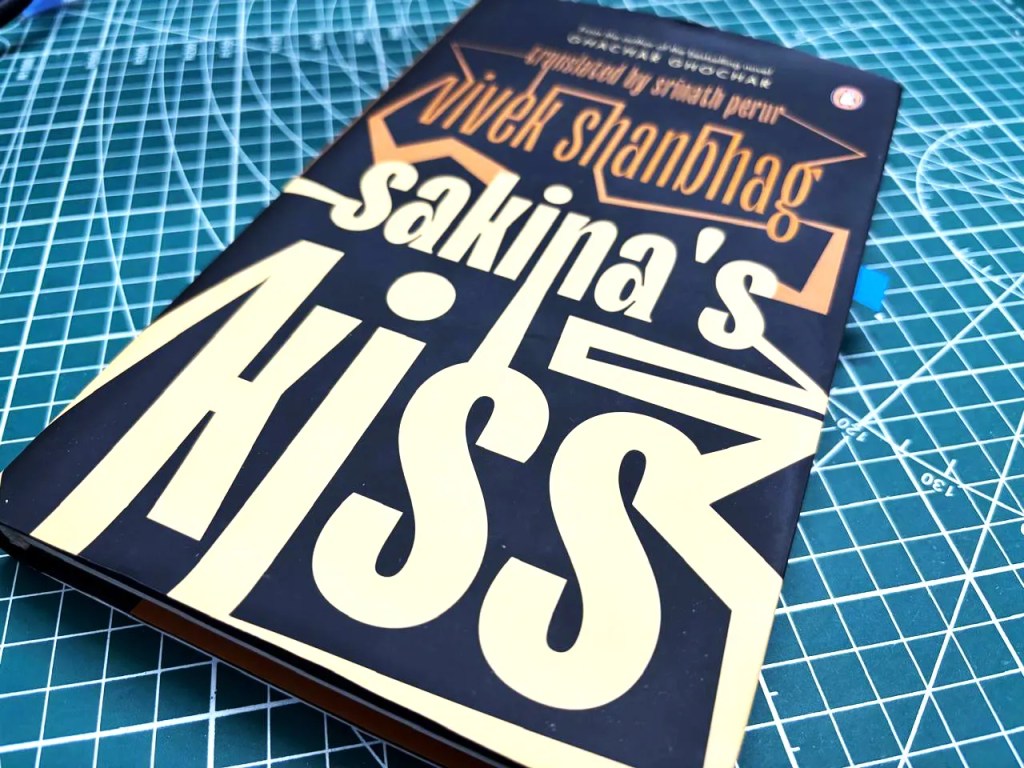

In one of the interviews, Vivek Shanbhag said he doesn’t write ideas or ideologies, but narrates characters with rich details and stories which emulate life. As a reader, once we finish reading a literary work, our mind tends to simplify the work into a couple of lines and brand it with a particular idea. Thankfully, the experience offered by a great work interferes with the task of simple summarisation and opens up many doors to explore the work with diverse perspectives. Sakina’s Kiss, in the way it is constructed, constantly throws the reader off track and makes them guess what they are dealing with as the novel unfolds.

Once again, Vivek narrates the story of an upper-middle-class family that goes through dramatic and unpredictable events which rattle the notions of family, relationships, and identity. The whole story is narrated by Venkat, whom Vivek refrains from casting as either a protagonist or an antagonist. The ‘truth’ presented in the novel is Venkat’s point of view, leaving the reader to trust or doubt him, or imagine the other side for themselves. It is like listening to a phone conversation where you can only hear one side of the story — in this case, an unreliable one too.

Vivek is a habitual offender who dismantles the comforting illusions of the familial system and is brave enough to hold a mirror in front of the naked emperor — or the head of the family. The novel begins with a knock on the door, which leads to an invasion of everything one thinks has nothing to do with their personal and family life — or at least that’s what the majority of the middle class in India believes. Through Venkat’s lens, he narrates and ridicules the urban life crisis with a few pages that almost capture the life of every modern IT professional today. We are living in the post-globalisation era, where the majority of middle-class families have overcome the financial crises that the previous generation faced for decades, and are equipped with overwhelming tools and technology — many unnecessary and capable of creating more chaos, crisis and contradictions slowly seep into an individual’s choices — if one still believes they truly have any. It decides what success is, which house one should buy, which progressive mask they should wear, which side they should take — left or right — whom to marry, and so on.

At the beginning of his emotional arc, Venkat is split between the feudalistic and capitalistic values of society, between small-town and cosmopolitan culture, between patriarchy and modern values. It is difficult to put Venkat in a black-and-white box, because he comes with a hundred shades of grey. Vivek uses the language of the mundane, the simple day-to-day, in this section to show the conflict brilliantly. The most intimate scene is almost caricatured with an ironic ending statement from Venkat, revealing one of his grey shades: “There is nothing exhilarating as taking possession, establishing authority. I wanted this ride to last forever.”

Venkat and Viji’s connection through a self-help book is nothing but absurd and comical, and also reflects the phenomenon of self-help book authors in the late nineties in India, and the socio-psychology behind it. Tiwari’s name, which comes as a fleeting mention in this novel, is influential on Venkat’s decision-making process — an interesting psychoanalysis of thousands of men who stepped into cities like Bangalore from small towns.

Viji, who sounds feminist and modern, is also vague — leaving it to the reader to decide if she is wearing one of those progressive masks or truly is one. There is no clarity on why she reads self-help books, because she seems like she doesn’t need one. She never quotes them or practises them like Venkat. Her sudden irritation with Venkat will also make readers wonder what changed — or remained unchanged — in their relationship. She is a woman of transition, neither entirely controlled by the system and men like her mother-in-law, nor rebellious like Rekha. She doesn’t care about posh schools and believes they are the root cause of her daughter’s rebellion, yet she takes Rekha’s side when a conflict arises. She is not obsessed with the upper class and CEOs as Venkat is. She sounds more practical, modern, and perhaps feminist, but does not contest patriarchy. These complex shades make the characters more real and prevent readers from jumping to conclusions about them.

The criminalisation of urban life and politicisation of the individual is the outcome of globalisation. The visit of the ‘uncles’ is the clash of two worlds: the criminal and the middle class. It is a clash of two different languages and worldviews. Middle-class families don’t have any tools to deal with criminalisation; when they encounter it, they freeze and panic. The fierce discussion about territorial votes, protection of women, and moral policing is brilliantly captured in a satirical portrayal of a serious exchange between the ‘uncles’ and Venkat. The intense discussion about whom to vote for reflects the heavy politicisation of individuals in recent times. Petty party politics sits in the centre of our living rooms, capable of creating cracks in relationships.

The relationship between father and daughter could be explained with one of Vivek’s comments: “Surveillance in the name of protection is control and authority; resisting it is protesting against authority.” Rekha’s rebellion, her disappearance, her choices, and her scathing remarks and replies to Venkat’s personality and behaviour are nothing but her protest against society. She is the representative of the odd ones who operate against the agency. Her visit to the village opens up an old world to us — a feudalistic community irked by changing times. Antanna still lives in a feudal era and wants to remain there forever. He and his brother (Venkat’s father) feel no guilt about grabbing land belonging to someone else. Irrespective of Venkat’s mother’s loyalty to the family and her multiple pleas to hand over the land to Ramana, they will not change. She doesn’t have a say in anything in that family. She lives in a system that refuses her space and dies while taking care of her husband’s coughing fits — a classic example of a woman conditioned by the patriarchy of the feudal era.

The mysterious character Ramana, in a way, influenced Venkat to seek conformity. He is a smart, rebellious figure who can’t fit into the family system. He and Rekha were too idealistic to fit into the strict framework of a society that seeks conformity. Venkat, his father, or his uncle cannot understand what Ramana or Rekha are seeking.

Vivek resorts to satire to explain the absurdity modern life faces every day. The chapter where the neighbours examine Venkat’s house after the burglary is hilariously absurd. There is no intense moment in modern urban life; everything can be ridiculed. One can take a selfie at the most inappropriate moment, or inquire about kitchen utensils while ignoring the gravity of a situation. Interestingly, all the unexpected events in the novel are left hanging and unresolved: Nanda and Raja’s visit, Rekha’s secret mission, Ramana’s disappearance, and the burglary. Venkat jumps from one to another without reacting to any of them. In fact, everyone ignores the intensity of the crisis and mimics a sense of normality by making endless cups of tea and dosas.

A great piece of literature is like a mirror. I saw myself in almost all the characters — in Venkat as a cautious father, in Rekha as a rebel in my youth. Sakina’s Kiss — the misinterpreted line from Ramana’s crow-foot handwriting — is the key to unlocking an important aspect of the novel. No one could read Ramana’s letter; it is interpreted in the way one can understand, but when someone reveals the truth, they are not ready to face it. Venkat, Viji, and Rekha face a state where they cannot understand each other. Venkat’s father and Antanna refuse to know the truth. The failure — or refusal — to communicate in the family leads to its disintegration. At times, property is more important than relationships; authority over the family, political correctness, and pseudo-intellectuality are capable of testing family bonds. Selfishness, ideology, patriarchy, liberalism, pseudo-intellectualism — it’s a long list that shakes the foundations of relationships now a days. Like Venkat, who is left alone at home to see his whole life in the almirah, we are also left to ask ourselves: what makes the family, and what breaks the family?

Leave a comment